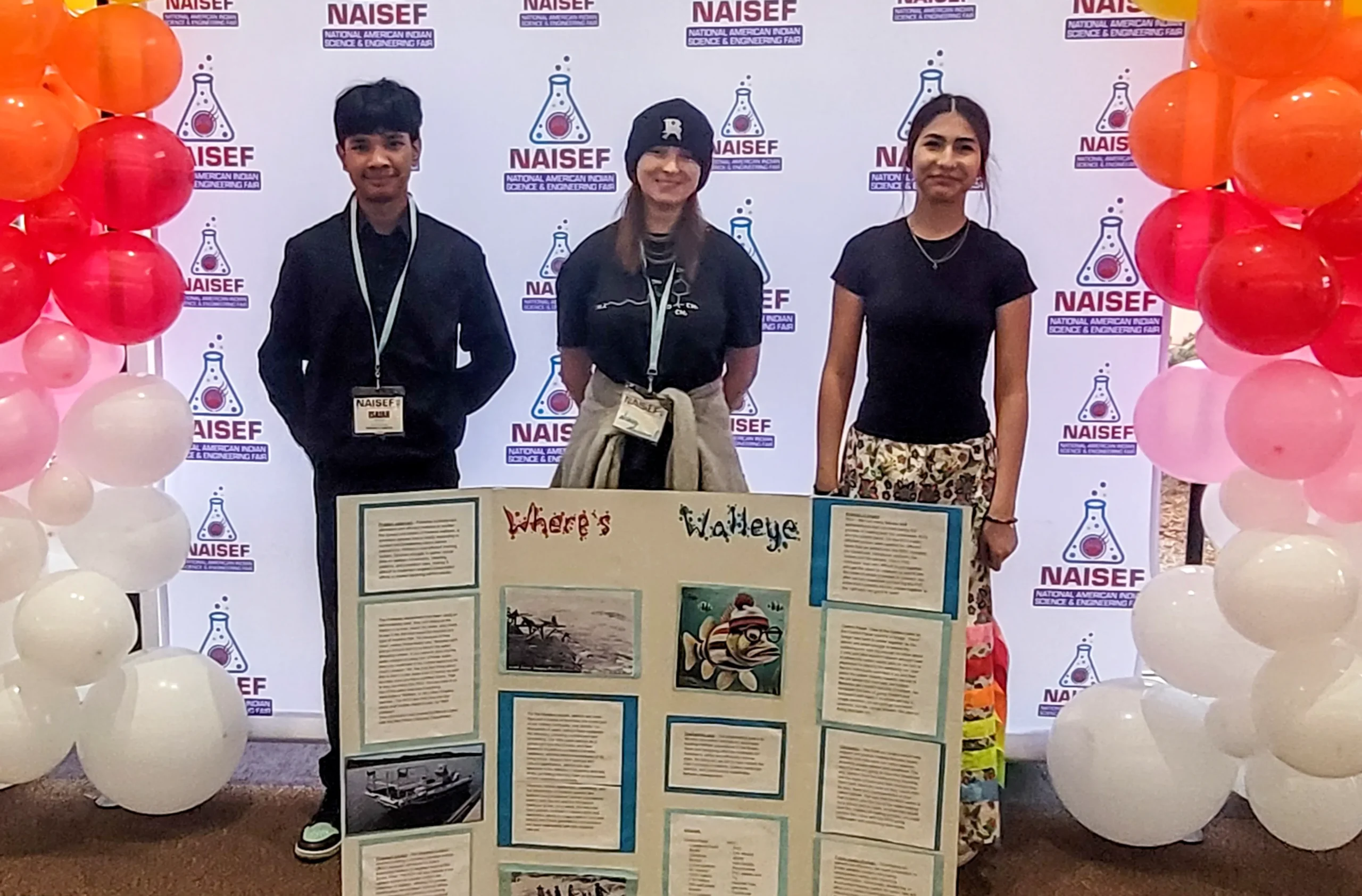

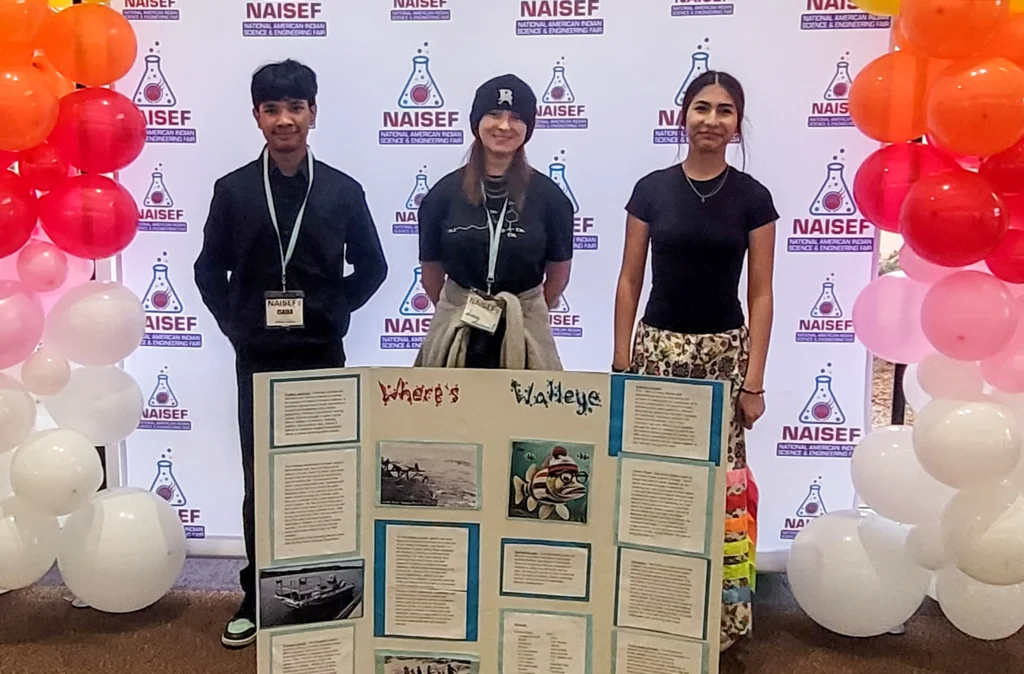

Lapwai Middle/Senior High School students, from left, Isaiah Painter, Nouah Macconnell and NaTalia Bisbee with their award-winning robotics project, “Where’s Walleye?”

Lapwai Education Association member Matthew Morgan has deep faith in his students. So when he heard about the National American Indian Science and Engineering Fair, he signed them up.

Never mind that competitors from other states had spent the better part of a year working on their projects, or that his students hadn’t even started theirs. Forget that he had no money to fund their efforts. Or that the competition was two months away. In Oklahoma.

Two months later, Morgan was jumping up and down in the back of an auditorium in Stillwater as his students were honored for their robotics work — not once, but twice.

Lapwai Middle/High School students NaTalia Bisbee, Noua Maconnell and Isaiah Painter created an underwater robot that hunts walleye, an invasive species that decimates the salmon so critical to the Niimiipuu (also known as Nez Perce) people.

“They went in just with a good idea and a good robot and a super positive attitude about it, and absolutely destroyed the competition, which is amazing to me,” he said. “It’s a huge testament to what not just Native students, but students here in Lapwai, are capable of.”

‘Anybody Can Figure It Out’

Morgan, who is originally from Lewiston, always longed to teach. But the profession presented a financial choice that he didn’t feel he could responsibly make.

“It just never made sense to stop earning six figures by building houses and working at the paper mill,” he said.

But a moment that could have been tragic proved transformative: Morgan was injured on the job. There would be no going back to his previous line of work. Morgan reached for the silver lining with both hands by enrolling in Lewis-Clark State College.

Matthew Morgan

His goal, always, was middle school. Educators break into three camps, Morgan explained. There are those who love the challenge of high school students. There are those who love the personalities and possibilities of elementary-aged children.

“And then there’s a couple of us that are completely off the rails ourselves, and we’re like, ‘Give me those weird puberty years,’ ” he laughed.

“They’re really just little kids in big bodies,” he said. “And they don’t know what to do with those bodies. So having that understanding and the compassion to help them figure that part out, in probably the most difficult years of education during their entire lives, has always been one of those things I have a big soft spot for.”

But even with that enthusiasm and understanding, Morgan had a difficult time finding a position — until serendipity swooped in. He ran into a fellow educator while shopping and she informed him that she had recommended him for a job in Lapwai teaching fifth grade. His application was accepted right away.

Just a few years after stepping into his first classroom, the pandemic hit. Morgan’s immune system was compromised by his accident, so his teaching partner took on the in-person segment of class and Morgan began creating science videos on YouTube.

“I would be in my garage and doing massive experiments,” he said. “Science experiments, mathematical experiments, breaking down all these big things.”

His garage experiments reminded him of his love of science and math, and he doubled down on his dream of teaching his favorite subjects to middle schoolers. After making it to Lapwai Middle/High School, he insisted on creating a robotics class.

Now, many of his students are on their second year of robotics instruction. His students are learning how to do everything from coding to soldering in his classes, but Morgan doesn’t believe in helicopter instruction.

“My favorite thing to tell my students is, ‘Anyone can figure it out,’ ” he said. “They hate me for it, but the onus is always put back on my students. Always.”

Chronic Underfunding Takes Its Toll

So far, Morgan’s robotics class has been funded by grants he applies for himself. It’s a situation many rural educators find themselves in thanks to the Idaho Legislature’s chronic underfunding of public education — a situation put in stark relief by the presence of Lewiston, located just 15 miles away.

In Lapwai, nearly 80% of the student population is Native. In Lewiston, Native students account for only 20%. Lapwai School District has been on a continuous improvement plan for years. Lewiston School District continuously embraces trailblazing teaching systems. Lewiston just built a new high school and career technical center. Lapwai students with a passion for science and math leave the local high school to continue their education in Lewiston.

When the Idaho Legislature refuses to do its job and instead relies on local taxpayers to make up the difference, rural schools suffer. Region 2 President and newly elected NEA Director Lindsey Smith said that puts dedicated educators like Morgan in the position of scrambling for resources.

Smith, who teaches in Lewiston, said the disparity can be jarring. “We recognize, being so close to some of these tiny rural communities, that when students leave rural communities for opportunity, it hurts the community,” she said. “So to continue ensuring that all students have access to high-quality, equitable education, we have to work together to strengthen and sustain our vital programs. And I think it just it comes down to: We need to fully fund our rural schools and provide access to these opportunities and resources that our students need to thrive, or we’re going to lose these rural communities — because we know that our public schools are the heartbeat of these communities.”

Where’s Walleye?

And yet, despite the economic hardships, the Lapwai School District has very little educator turnover. Smith, who mentors student educators, said the new educators who spend time in Lapwai immediately understand why.

“They get the full perspective of just how interesting it is and how everything is about community and culture,” she said. “And I love that it’s consistent. Every time a new student teacher comes to me, they say, ‘Oh, it’s amazing out there. It’s challenging at times, but the community really shines through.’ ”

The community definitely shines through for Morgan, who is white. He recently completed his master’s thesis, focusing on how STEM education aligns with traditional ways of knowing. “Maybe we should stop trying to invent new science and just listen to the First Peoples, because they’ve been trying to do it this way for 10,000 years,” he said.

For centuries, part of that culture has been stewardship of the land, including food sources like salmon. Walleye, which were introduced into the area in the 1960s, are a threat not just to salmon, but to Niimiipuu cultural heritage. So when Morgan talked to the local fisheries department about the threats facing salmon, he knew his students would have a natural interest in making a difference. And they wouldn’t even need to reinvent the wheel to do it – they had already developed the idea of a robot that could clean the tanks used to hold fish.

When Morgan brought the walleye problem to the three students, “they just went wild, absolutely went crazy,” he said.

Their robot is an underwater remotely operated vehicle, or ROV, that places the user in control of the robot. There is a live view camera on the robot as well as sonar to locate the walleye. The students used PVC pipe and wood found in Morgan’s garage to complete the prototype. When the prototype was one bolt short, he went back to his house to locate one the students could use.

After a month and a half of work, the students traveled to Oklahoma with their project, “Where’s Walleye?”. Morgan was hoping for an honorable mention of some sort. Instead, his students received a second-place finish in their division — usually, only first place is awarded in their division. Morgan later discovered his students received the award due to a split decision among the judges (Morgan called the first-place winner “Einstein incarnate”).

Morgan and his students were still glowing when their names were called again, this time to receive the Heritage Award, which is given to students who help their native culture thrive through STEM. Morgan had entered their project for the Heritage Award with a belief and a prayer.

“The junior division doesn’t win the Heritage Award, but I put their name in the hat for it anyways because I’m like, ‘They’re going to win everything,’ ” he said. When the students’ names were called, Morgan said, he was swamped by other educators asking how a junior division team pulled off such a prestigious prize.

“I was so incredibly proud, and I still am,” he said. “What they did in a month and a half — they had an almost perfect clean sweep against projects that had been going on for six to eight months, and against projects that had thousands of dollars in support backing them.”

The students were recognized by the tribe at the Nez Perce General Council Meeting in early May. Isaiah, one of the students, spoke to the council about the importance of making the robotics class available in high school.

During Morgan’s interview with IEA Reporter, his teaching partner was unboxing a new laser engraver for the students. Morgan will continue writing grants to subsidize his practically nonexistent budget, but the payoff is worth the extra work.

“I know these kids can do amazing things,” he said. “Even though they’re these Native kids on a reservation, and we’re in a state — and an area of the state — that does not have a very high opinion of not just Native students, but Natives as a whole. And these kids crushed it. They just destroyed.”

Learn More About Becoming a Culturally Proficient Educator

Idaho Education Association offers avenues to learn more about cultural proficiency and how it makes a difference in students’ lives.

- Ask your local president or region president about getting involved in Leaders for Just Schools

- Take a class through the Center for Teaching and Learning, including equity-focused classes at the upcoming Summer Institute in Lewiston

- Talk to your local president or region president about joining IEA’s Human and Civil Rights Committee